Walking the Trail, you may pass a stream called, "Shooting Creek". There are many, and the name does not refer to the water cascading down the mountainside, but to the stills that were fiercely defended as an alternative source of cash after blight killed the big American chestnut trees, taking with it the mainstay of the mountain family's existence. Just imagine what once was ours: before the blight, one-fourth of the trees in Appalachia were American chestnut. At the time, a hundred feet tall was not an uncommon size for chestnut, and the small sweet nuts were preferred by most of the wildlife from birds to bears.

The destruction of the American chestnut began with a blight imported on Oriental nursery stock shortly after the turn of the century, and proceeded steadily south- and west-ward from New York through the eastern states in spite of all efforts to halt or delay its spread. By the Great Depression, the chestnut forests of Virginias Blue Ridge Mountains were dead; by the early 1950s the last large groves in West Virginia had also succumbed.

Everywhere the forests were haunted by tall gray ghosts that covered some mountains so completely that the rural folk described them as giant porcupines. However, the lumber was still valuable, straight as the yellow poplar and nearly as strong as oak, but much lighter, more easily worked and more versatile. Chestnut bark was the preferred source of tannins for tanning leather. So the standing dead timber was harvested, except in remote areas where some standing dead trees may still be found. Chestnut, like locust, is highly resistant to rot.

Old-timers speak of the era before the blight in mythic terms, "We had a world of chestnuts." Because they bloom after the last frost, the nut crop was 100% dependable. Late in September through early October when chestnuts dropped, all energies were directed toward their harvest, and just about every-one dealt in chestnuts. In the mountains, school did not begin until after chestnut harvest. Families who did not own groves collected what fell in the nearby open woods where underbrush had been cleared to facilitate nut gathering.

Transported by horseback or wagon to the country store and thence to the railroad, the first sweet nuts of each season brought 10 cents a pound, when sugar and meat were 4 and 5 cents a pound, the best grade of flour was 49 cents for a 25 pound bag and $1.75 was a daily wage. On a good day an adult might collect as much as 100 pounds. Many a mountain family earned enough at chestnut harvest to provide the cash needs for the year, including schoolbooks, clothing, treats, and all food not produced at home. Chestnuts were the single biggest source of income in the mountains, and for the poor folks, often the only source.

Following harvest they turned the hogs out in the woods to fatten on chestnuts. What the hogs missed was food for the abundant wild game which hunters used to supplement the larder. As the chestnuts died out, so did the independent existence they had supported. Some found work at the sawmills. Large numbers left the home place for the first time to work in coalmines. Those who could not or would not work for others turned to moonshining.

Today only a few big chestnuts survive within the natural range. The rest are mostly roots that the underground environment protects against blight, and their shoots, which inhabit the understory. The shoots are sheltered from the wind-born blight by taller trees but are stunted for lack of sunlight, unable to flower and produce nuts. Now it is possible to begin American chestnut recovery of the canopy slot at carefully selected sites within the former domain; management should play an important role, and the interested public may participate in the rescue of the species (Castanea dentata).

November fog photo of a rare "Large Surviving" American Chestnut in the Nantahala National Forest, North Carolina. Large trees in the natural range are generally thought to survive due to one or more of hypovirulence, ideal site, and limited resistance to blight. This particular tree is significant because it is surviving in a harsh environment where growing conditions are stressful and hypovirulence is thought to be ineffective.---Photo by Ed Greenwell

Studying chestnut blight and the ecology of forest chestnuts since the 70s, breeding all-American intercrosses, and grafting for blight resistance, Gary Griffin, Professor of Plant Pathology at VA Tech, and John Rush Elkins, Professor of Chemistry at Concord College, WV, founded the American Chestnut Cooperators' Foundation. In a nutshell, their plan is an integrated management approach, combining ideal sites managed for American chestnut, grafting for blight resistance and the manipulation of a naturally occurring biological control.

When chestnuts are released on newly clearcut lands, they compete well at first, growing as rapidly as any other tree, and bearing nuts within a few years. Then the blight strikes and the trunk is killed, while at its base, new sprouts appear. Whenever a sprout is not browsed back by deer and rabbits or shaded out by other trees, it can make a nut-bearing chestnut tree within 4 or 5 years. Once again blight will kill the tree, and once again its roots will send up more sprouts.

Each time this cycle is repeated, the chestnut shoots compete against greater odds because the other trees are not affected by blight. The chestnut shoots, being the newest growth available, are more heavily browsed; and because of the competing hardwood trees, they receive less and less sunlight. Within 10 years after clearcutting, most of the chestnuts are dead, roots and all. Many clearcuts (and other openings, caused by storms, fire, pests and disease) in prime chestnut country age past the deadline, we are losing the valuable rootstocks that could hold these sites for a revival of American chestnut.

Ideal American chestnut habitat is found on sloping lands at low to medium elevations, in coves facing east to north, with many chestnut stems, acid, sandy-loam soils and full sunshine. Good site indicator trees are tulip poplar, cucumber magnolia and red oak. When openings occur on these sites, they should be managed for American chestnut recovery; no other use could match the potential benefit to the forest community. Management involves cutting out competing hardwoods within 10 feet of chestnut stems every other year. When this is done, continuous cycles of blight cause hypovirulence, a virus infection of the blight fungus. Typically the blight fungus enters the inner bark through wounds, forming sunken cankers that expand rapidly, kill the cambium and girdle the tree within a year. In contrast, hypovirulent strains of the blight fungus make swollen cankers grow slowly; they are superficial, confined to the outer bark, and do not threaten the trees life. Hypovirulence can increase chestnut survival up to 5 years and establish continuous nut production to feed the wildlife on a managed site.

For a forest site to produce large chestnut trees, blight resistant stock must be grafted there, then the first blight cankers on the grafts must be inoculated with hypovirulent strains of the blight fungus. This combination has produced biological control of blight on three American chestnuts grafted in the Lesesne State Forest (Nelson County, VA) in 1980 and inoculated in 1982 & 1983. They are thriving amidst a sea of blight, averaging a meter growth per year, and have been producing nuts since 1989.

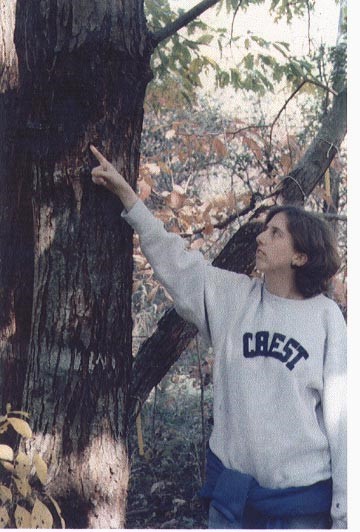

Tallest tree in the background is 61 feet. Nancy Robbins, who studied the spread of hypovirulent strains on this tree, is leaning against a blight-killed stem directly in front of it. Nearly all the chestnut stems in this plantation which were not grafted with blight resistant scions are continuously killed by blight and re-sprout from the stumps.

This is the example you may help to reproduce. As you ramble through the woods, keep an eye out for American chestnuts struggling to survive in new forest openings that meet the ideal specifications. Choice of site is very important to avoid additional environmental stresses that could upset the delicate balance of blight control. On public lands, you may contact the Forest Service for permission to adopt the site and manage it for American chestnut recovery.

We hope you may be able to join in our efforts to save the best parts of the forest for American chestnuts. There is enough work to be done to keep us all out of retirement. It promises an unparalleled benefit to the environment, for our descendants legacy.

---Lucille Griffin American Chestnut Cooperators Foundation

02/04/2024